Shadow Variation in American Beauty

- Stephen Gerringer

- Aug 10

- 7 min read

Updated: Aug 13

The shadow is one of the many archetypes that populate our psyches. According to Jungian psychology, the shadow is frequently associated with one’s personal unconscious: everyone has a shadow, but every shadow is different, depending on its contents:

The shadow is, so to say, the blind spot in your nature. It’s that which you won’t look at about yourself ... It is made up of the desires and ideas within you that you are repressing—all of the introjected id. (Joseph Campbell, Pathways to Bliss, 73)

Shadow is present when we refuse to face certain things about ourselves, such as a repetitive, self-destructive behavior. The more we struggle to maintain our denial, the more life conspires to muck up the works, leaving us at the mercy of events seemingly beyond our control.

Unfortunately, I don’t know what my shadow contains, as it is unconscious to my waking ego. One can't see one’s own shadow full on. We have to catch it obliquely, often through the eyes of others (easier to see someone else’s shadow than my own).

Another clue comes from paying attention to what disturbs us about others. When I react to individuals or situations with disproportionate anger, that emotion is fanned by shadow projections, allowing me to hate those parts of myself without actually owning them.

A valuable tool to help recognize the ways shadow impacts those living unexamined lives comes to us courtesy of the silver screen. This week’s essay highlights one film that has enhanced my own understanding. (Spoilers Ahead)

One can't see one’s own shadow full on. We have to catch it obliquely, often through the eyes of others

Shadow puppet

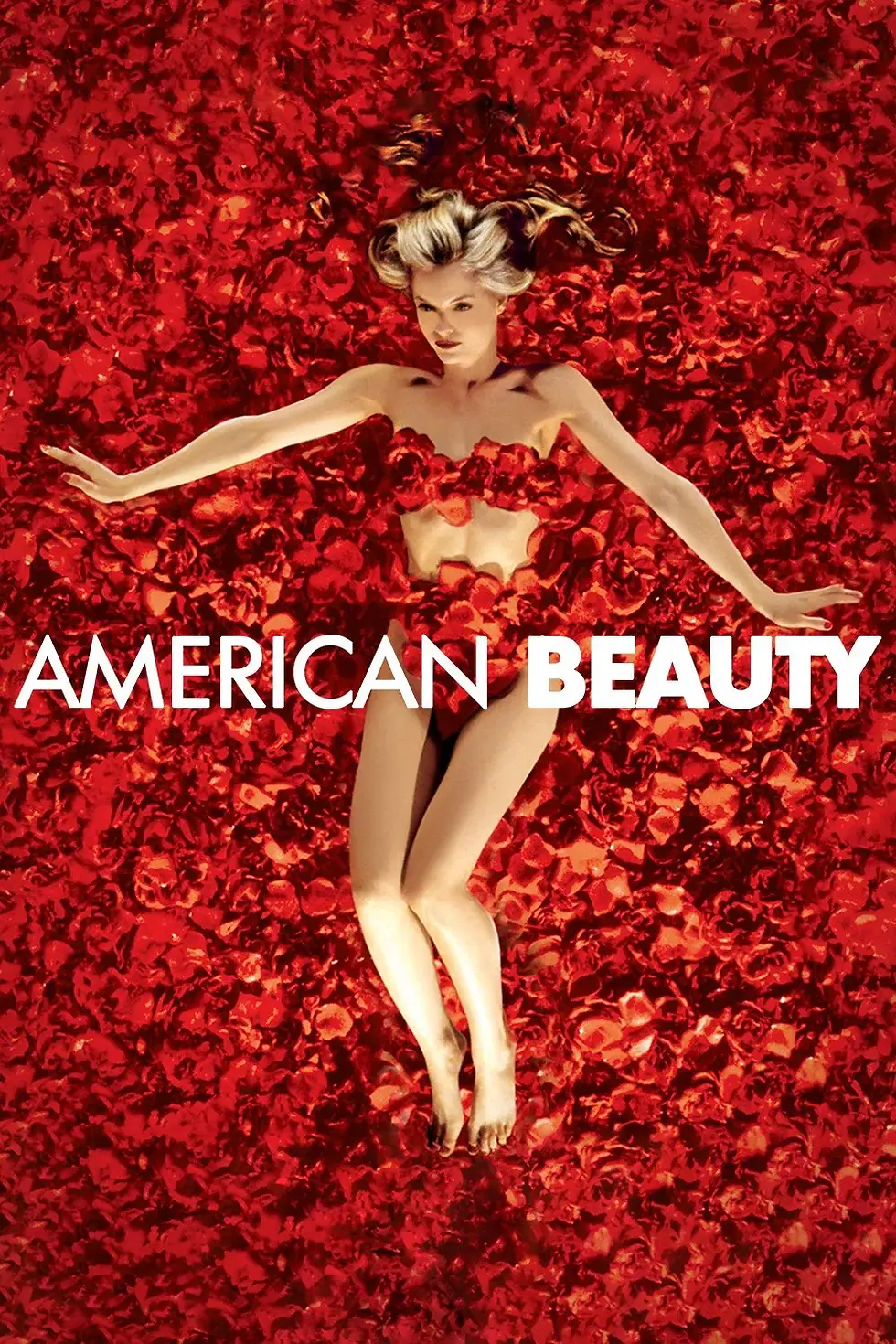

American Beauty, which swept the Academy Awards the spring of 2000, focuses on forty-two-year-old Lester Burnham (Kevin Spacey), his wife Carolyn (Annette Bening), and their teenage daughter, Jane (Thora Birch). The Burnhams appear to be a comfortable middle-class family living the American dream; all however, is not what it seems.

Lester, a well-paid advertising executive in a soul-deflating job, doesn’t make waves in life. His wife and daughter consider him a loser, a perception Lester does not dispute, until he falls for Angela (Mena Suvari), his daughter’s best friend on the high school cheerleading squad—a siren call that triggers a full-blown midlife crisis.

Surreptitiously eavesdropping on Angela as she tells Jane she’d consider sleeping with her dad “if he built up his arms and chest,” Lester quits his job, begins lifting weights in the garage, buys the muscle car he dreamed of as a teen, applies for a low paying, low stress job at a local fast food outlet, and starts smoking marijuana he gets from the boy next door.

What deepens this beyond mere farce is the creepy infatuation with his daughter’s teenage schoolmate, and Lester’s announcement, shared in a voiceover at the beginning of the film, that he will be dead in exactly one year.

Shadow of doubt

Lester is far from the only character pushed around by their shadow; projection also plays a part in the relationship between Jane and Angela. Jane sees herself as plain and dreary, in contrast to bright and shiny Angela, who is constantly recounting her sexual escapades. As Jung observes:

It is not uncommon that friendships are formed in which one partner is the shadow of the other. (C.G. Jung, Children’s Dreams: Notes of the Seminar Given in 1936 - 1940, 129)

We do glean a huge clue to Angela’s shadow when she tells Jane “there is nothing worse in life than being ordinary”—which is why Angela is shattered the final evening of Lester’s life, when Ricky Fitts (Jane’s boyfriend and her dad’s pot connection) tells her she is “boring, and you’re totally ordinary – and you know it.”

Stung by this verbalization of what she fears most, Angela flees downstairs in tears, and right into Lester’s arms. As he lowers her to the sofa, Angela seeks reassurance, asking, “You don’t think I’m ordinary?”

Shadow Boxing

The shadow ... swallows those things that would be dangerous for you to express. (Pathways to Bliss, 74)

While there are similarities as well as differences in how shadow manifests in Angela’s and Lester’s lives, the tightly wound next door neighbor, Colonel Fitts (Ricky’s disciplinarian father), presents a far more jarring illustration of what can come from ignoring one’s shadow.

Our first clue comes early, when Fitts fumes about a gay couple in the neighborhood. As the film progresses, he spies Lester signaling Ricky to “call me,” prompting Fitts to snoop in his son’s room. There he finds and plays a video trained on the garage windows next door, which Ricky had left running when he dashed over to deliver weed to Lester during a workout. Unfortunately, the camera view is partially obscured. The audience knows Ricky has knelt to roll a joint on the bench as Lester, clad just in gym shorts, takes a toke and leans back to enjoy the high; Fitts, however, sees his teenage son kneeling and leaning forward, head obscured, as their apparently naked, middle-aged neighbor smiles in ecstasy, and so connects the dots to draw a picture that reflects his own repressed shadow.

The enraged father confronts Ricky and kicks him out of the house. Later that night, when Lester sees the colonel outside in the pouring rain looking dazed, he raises the garage door and compassionately wraps his neighbor in a towel. Asked where his wife is, Lester, who had earlier caught Carolyn in a tryst, replies, “Our marriage is just for show. A commercial for how normal we are, when we’re anything but”—which Fitts takes as confirmation of his worst suspicions.

Expecting confrontation, the audience is surprised when the troubled man suddenly kisses Spacey’s character full on the lips! Lester gently tells his neighbor he has the wrong idea, and the distraught colonel wanders out into the night. That rejection drives him right back into denial, with ultimately tragic consequences for our protagonist.

This episode is almost a textbook example of shadow projection in the extreme: Fitts projects the contents of his shadow, and the accompanying self-loathing, outward, onto an “Other”—in this instance, Lester. Harming that Other can serve as a substitute for destroying what one most fears in oneself.

So, is there no escaping Shadow’s grip?

Seeing through the dark

Of course, what makes anything shadow is that it’s outside the light of conscious awareness. Once I see it, it's no longer shadow, and no longer has the power to direct my behavior.

Lester Burnham spends most of the film channeling adolescent fantasies that he abandoned when life forced him to grow up, which have remained frozen in his personal unconscious ever since: driving a fast car, working an undemanding job, indulging in antiauthoritarian snark, getting stoned with the neighbor kid, and, yes, even bedding the cheerleader

. . . almost.

The moment of truth arrives after the encounter with Fitts. Lester enters the kitchen and hears the object of his lust crying in the living room. Angela explains that she and Jane had argued because Angela thinks he’s sexy. Hearing this, Lester makes his move.

(This is cringe-inducing, intentionally so. At the start of the film, Jane looks relatively innocent and naïve next to her glamorous, seductive friend. As Jane experiences her own sexual awakening, her character starts wearing more and more makeup, while Angela wears less and less, looking ever younger and more childlike.)

As Lester unbuttons Angela’s blouse, she confesses this is her first time. He thinks she’s joking, but disbelief gives way to horror as projections pop (anima, as well as shadow, though that’s a whole other MythBlast), and he finally sees her not as an object, but a vulnerable teen about to be violated by her best friend’s dad. Face to face with his own shadow, the spell is broken; what follows is the first authentic, compassionate exchange either character has experienced all film.

Awareness depotentiates shadow:

You are to assimilate the shadow, embrace it. You don’t have to act on it, necessarily, but you must know it and accept it. (Pathways to Bliss, 80)

Of course, this is Hollywood, so it’s all epiphany, absent the discipline and hard work necessary for true shadow integration*; nevertheless, as the final moments of his life creep up and cut short his redemptive arc, we see Lester gazing with love and affection at a photograph of Jane, Carolyn, and himself in happier times.

There is far more to American Beauty, a symphony of symbolism and cinematography that still speaks to me. Rave reviews have in recent years given way to more nuanced analysis; nevertheless, the film’s poetic exploration of variations on the Jungian shadow remain relevant today.

*For more on integrating archetypal images, read “Cultivating Gratitude Through the Transcendent Function”, a MythBlast essay by Craig Deininger.

MythBlast authored by:

Stephen Gerringer has been a Working Associate at the Joseph Campbell Foundation (JCF) since 2004. His post-college career trajectory interrupted when a major health crisis prompted a deep inward turn, Stephen “dropped out” and spent most of the next decade on the road, thumbing his away across the country on his own hero quest. Stephen did eventually “drop back in,” accepting a position teaching English and Literature in junior high school. Stephen is the author of Myth and Modern Living: A Practical Campbell Compendium, as well as editor of Myth and Meaning: Conversations on Mythology and Life, a volume compiled from little-known print and audio interviews with Joseph Campbell.

This MythBlast was inspired by The Hero With a Thousand Faces and the archetype of The Shadow.

Latest Podcast

This lecture, "Mythology - The Path (Part 1)", was recorded in 1980 at Yellow Springs, Pennsylvania. In it, Joseph Campbell discusses archetypes that guide us toward deeper inward experiences. He explores the Sanskrit word for "path," Marga, using it as a mythic metaphor for life. Drawing on Jungian psychology, Campbell expands on this theme to offer deeper insights into mythology. Host Bradley Olson introduces the lecture and provides commentary at its conclusion.

This Week's Highlights

"The shadow . . . swallows those things that would be dangerous for you to express."

-- Joseph Campbell

%20BB.png)