The Zone of Unknowing: Auschwitz and the Cinema of Prophecy

- Teddy Hamstra, PhD

- Nov 16, 2025

- 7 min read

Jonathan Glazer’s The Zone of Interest (2023) rattled me so thoroughly that I found myself returning twice more to the same theater where I first witnessed it—in December 2023—as if to the site of a haunting. Many films wrestle with the problem of evil, but very few are worthy of being labeled a cinematic theodicy. Cinema, and its sister arts, have reckoned with how—or whether—it is even possible to depict the Holocaust. A genocide of debased brutality on an industrial scale that defies our everyday comprehension, the “Final Solution” enacted by the Third Reich between 1942 and 1945 resists the capacities of art to render or contain. The unflinching realism of Tim Blake Nelson’s The Grey Zone (2001) and the ultimately redemptive arc of Steven Spielberg’s Schindler’s List (1993) offer two distinct attempts to place the Shoah within a celluloid frame. The Zone of Interest aspires, through the plasticity of filmmaking itself, to alchemize a mythic image of prophecy (Spoiler alert).

A prophetic heritage

The Western world is the inheritance of the prophets. From the admonitions of the Hebrew scriptures to the political theater of today, the prophet archetype is ever-present: the one who sees what others refuse to see, crying out from the margins, whose voice unsettles the comfortable. Prophetic voices become cultural forces unto themselves—not limited to religion, but emerging in moments of moral emergency. American history is punctuated by this: from John Brown and Frederick Douglass, to the twinned prophetic voices of Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X—Gemini-like in their shared purpose but divergent methods.

Europe produced its own secular prophets, from Nietzsche’s proclamations of the death of God to Marx’s vision of revolutionary upheaval and Jung’s warnings of psychic fragmentation. And, in the darkest of incarnations, Adolf Hitler demonstrates the catastrophic perversion of prophetic charisma. Mein Kampf, fevered and deranged, nevertheless functioned as a prophetic text whose visions were enacted with genocidal precision.

Ambivalence defines Joseph Campbell’s relationship to the Prophet. In an early essay, he cautioned that “overwhelmed by his own muse, a bad poet may fall into the posture of a prophet—whose utterances we shall define (for the present) as ‘poetry overdone,’ overinterpreted—whereupon he becomes the founder of a cult and the generator of priests” (The Mythic Dimension, 25). From Creative Mythology onward, however, his tone shifted to an optimistic insistence that “all mythic images are rendered by what are called seers or prophets; today we would call them artists. The artist is one who’s opened the eye of vision and sees past the phenomenal forms to the morphological principles that animate them, and then renders them to us (Myth and Meaning, 168).” Campbell’s evolution is instructive for reading Glazer’s film. If the modern artist inherits the prophetic mantle, then cinema—at its most daring—can perform the prophetic function: to pierce ordinary perception, and to mythologically disrupt linear time.

If the modern artist inherits the prophetic mantle, then cinema—at its most daring—can perform the prophetic function

Zones of interest: filmmaking as oracle

The Zone of Interest positions us not inside a mythic underworld, but at its perimeter. From the chilling vantage point of Auschwitz’s “neighbor,” we traverse the household of its kommandant, SS Obersturmbannführer Rudolf Höss, and his family. Glazer moves through three distinct cinematic modes that shape our perception, conditioning us for the film’s final, prophetic rupture in time. The first technique is rendered with the flat, affectless clarity of surveillance footage—what I think of as “Ring Camera realism.” Glazer portrays evil not through slaughters or ideological tirades, but through the numbing rhythms of suburban middle-class routines. It would be easier if Höss (personally responsible for the slaughter of over one million Jews, gypsies, queer and disabled people) resembled a hydra or Oceanic sea-beast—as if evil only ever announced itself with grotesquery or supernatural aura. He is life-sized, unfortunately human. The dreams of Rudolf and Hedwig Höss, couched though they are in the specific Nazi ideology of Lebensraum, are nevertheless, and queasily, recognizable: a comfortable house, a pool in the backyard, a jungle gym for the kids. Glazer’s camera asks, with prophetic disquiet, How different are these people from us?

The second aesthetic is that of sensory disturbance. Glazer introduces slow-dissolving images—flowers and other shapes that bloom and fade—paired with a soundscape that is less score than lamentation from composer Mica Levi. These sequences are impressionistic prophecies that refuse spectacle yet summon horror through absence.

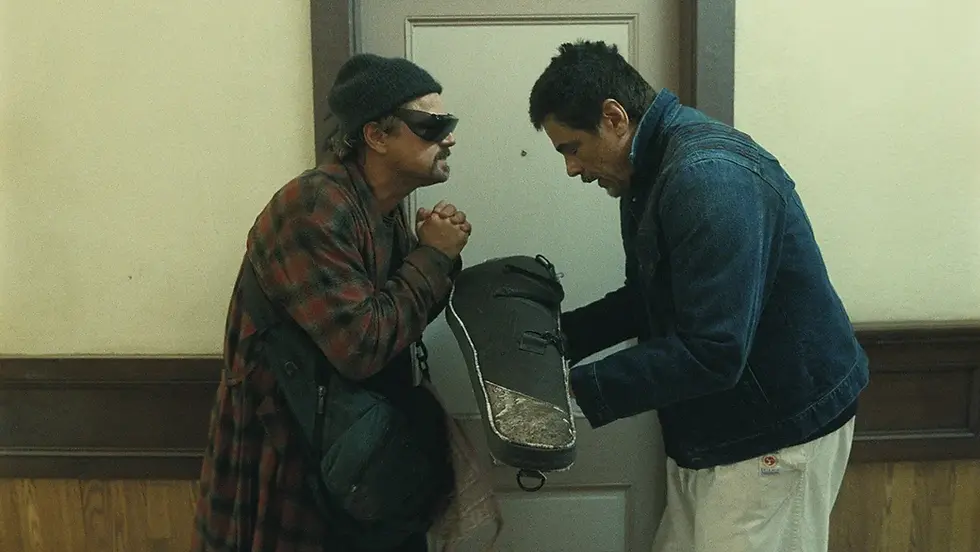

Filmed with night-vision technology, the third mode follows a young, Polish servant girl of the Höss household. In a mythic gesture to Hansel and Gretel, she leaves literal breadcrumbs, small offerings of sustenance for the prisoners at surrounding labor sites—a quarry, a railroad junction. Neither prophet nor savior, she is simply a human being who enacts a minor defiance against the machinery of death. A reminder that even in the darkest architectures of violence, some refused to avert their eyes and turned towards care, however small.

These modes—domestic realism, abstract sensory disturbance, and nocturnal resistance—work in concert. Without these preparatory movements, the film’s final rupture would arrive as mere gimmick. With them, it lands as revelation.

A cleft in cronos: myth, history, and the visionary

Telephoning his wife (annoyed at being awoken from sleep) during a banquet at which he is so bored all he can think about is how he would go about gassing the Nazi Party guests with Zyklon B, Hoss informs her of his grand achievement. Heinrich Himmler and Adolf Eichmann have drawn up a plan called Aktion Höss. During this namesake Operation, he will oversee the deportation and liquidation of nearly half of Hungary's Jews (some 420,000) in little over two months; in terms of the rapidity and efficiency of the killing, it is one of the most extraordinary crimes of the Holocaust. He then descends a bureaucratic staircase.

Midway down, he begins dry heaving, but is incapable of actually vomiting. For the first time, a crack appears in his impenetrable psychopathy. At the base of the stairs, he pauses before a corridor, illuminated only by a small, distant light. He gazes toward it, and, without warning, time dislocates. As if through a mystic portal, we have slipped into present-day Auschwitz, preserved as a museum and memorial. The lighting is fluorescent, an atmosphere sterile in its reverence. Custodial staff mop the crematoria floors and vacuum hallways where mountainous piles of shoes, suitcases, and other relics of lives extinguished are displayed. Following these caretakers of memory, we are watching history’s afterlife. The living perform the quiet, repetitive labor of remembrance, preserving the traces of those whom Höss sought to eradicate.

Several minutes elapse, and Höss stands exactly where we left him, staring into the cinematic void. Was this glimpse into the future a prophetic vision thrust upon him, or does the rupture belong to us? One reading is that despite his bureaucratic efficiency and pride in the machinery of extermination, history will instead preserve the memory of his victims. Or, is Glazer showcasing, through cinematic quietude, how the power of memory itself can withstand even the most violent attempts at erasure? Prophecy, in The Zone Interest, incarnates not as redemption or justice, but as endurance.

If ancient prophets warned their communities of impending disaster, Glazer uses cinema to warn us against the numbing of perception—against the normalization of evil through proximity and routine. Cinema itself becomes the medium of prophecy. Campbell’s later claim that the modern artist inherits the role of the prophet feels especially resonant here. If the artist, as Campbell writes, “opens the eye of vision” and “renders it to us” (Myth and Meaning, 168), then Glazer’s film is an act of prophetic seeing: it forces us to confront not the spectacle of genocide, but the structures that enable its horrible invisibility.

Prophecy, in myth, arrives through dreams, visions, or sudden fissures in time. The Zone of Interest offers one such cleft in chronos—but it does not grant closure. It leaves us suspended between genocide’s occurrence and remembrance. The light at the end of the corridor remains distant, a cloud of unknowing where myth and history brush against each other but refuse integration. As the credits roll and Levi’s score wails into the dark, we are left uncertain as to whether we have glimpsed a warning, a judgment, or, maybe, the prophetic persistence of memory. Glazer’s film obliquely, yet stirringly, asks the question to all of us modern-day mythmakers: might mythology itself be the work of being the custodian of the world’s memory?

MythBlast authored by:

Teddy Hamstra is a writer and seeker in Los Angeles. He is the recipient of a PhD from the University of Southern California, where he completed and successfully defended a dissertation entitled 'Enchantment as a Form of Care: Joseph Campbell and the Power of Mysticism.' Recently, Teddy has been working for the Joseph Campbell Foundation, spearheading their Research & Development efforts. As an educator and research consultant for creatives, Teddy is driven to communicate the wonder of mythological wisdom in ways that are both accessible to, and which enliven, our contemporary world.

This MythBlast was inspired by Myth & Meaning and the archetype of The Prophet.

Latest Podcast

C.J. Macias is a big wave surfer, healer, and teacher whose life feels as mythic as it is deeply human. Featured in HBO’s Emmy Award–winning series 100 Foot Wave, C.J.’s journey stretches from the beaches of Florida, where he first surfed with his dad, to Nazaré, Portugal, home of the largest waves on earth. Along the way he has faced devastating wipeouts, near-death moments, and the kind of initiations that strip life down to its essence. In 100 Foot Wave, we witness not only the danger and beauty of Nazaré, but also the brotherhood among surfers, the intimate dance with fear, and the transformation that comes from surrendering to the ocean’s immense power. In this conversation, we explore C.J.’s path, his call to big waves with Garrett McNamara, his evolving relationship with fear and the unknown, the ocean as teacher, and how Joseph Campbell’s vision of myth resonates with his own path.

This Week's Highlights

“All mythic images are rendered by what are called seers or prophets; today we would call them artists. The artist is one who’s opened the eye of vision and sees past the phenomenal forms to the morphological principles that animate them, and then renders them to us.”

-- Joseph Campbell

Myth and Meaning, 168

%20BB.png)